Long before the iron horses roared and screamed across the land, their wheels cutting through ancient hunting grounds, before men with axes came to cut down the tall cedar trees and carve roads through the wilderness, the people of the mountains lived in harmony with the forest spirits. They understood what many have forgotten: that the world is alive, breathing, watching.

They called the land the Great Breathing Earth, for every tree held a spirit in its roots, every stream carried a voice in its current, and every stone remembered the songs sung over it. The people walked lightly upon this living land, taking only what they needed, giving thanks for every gift received. They knew that balance was sacred, that the relationship between hunter and hunted, between human and forest, was a delicate dance that must be honored with every breath.

Click to read all American Cryptids & Monsters — creatures of mystery and fear said to inhabit America’s wild landscapes.

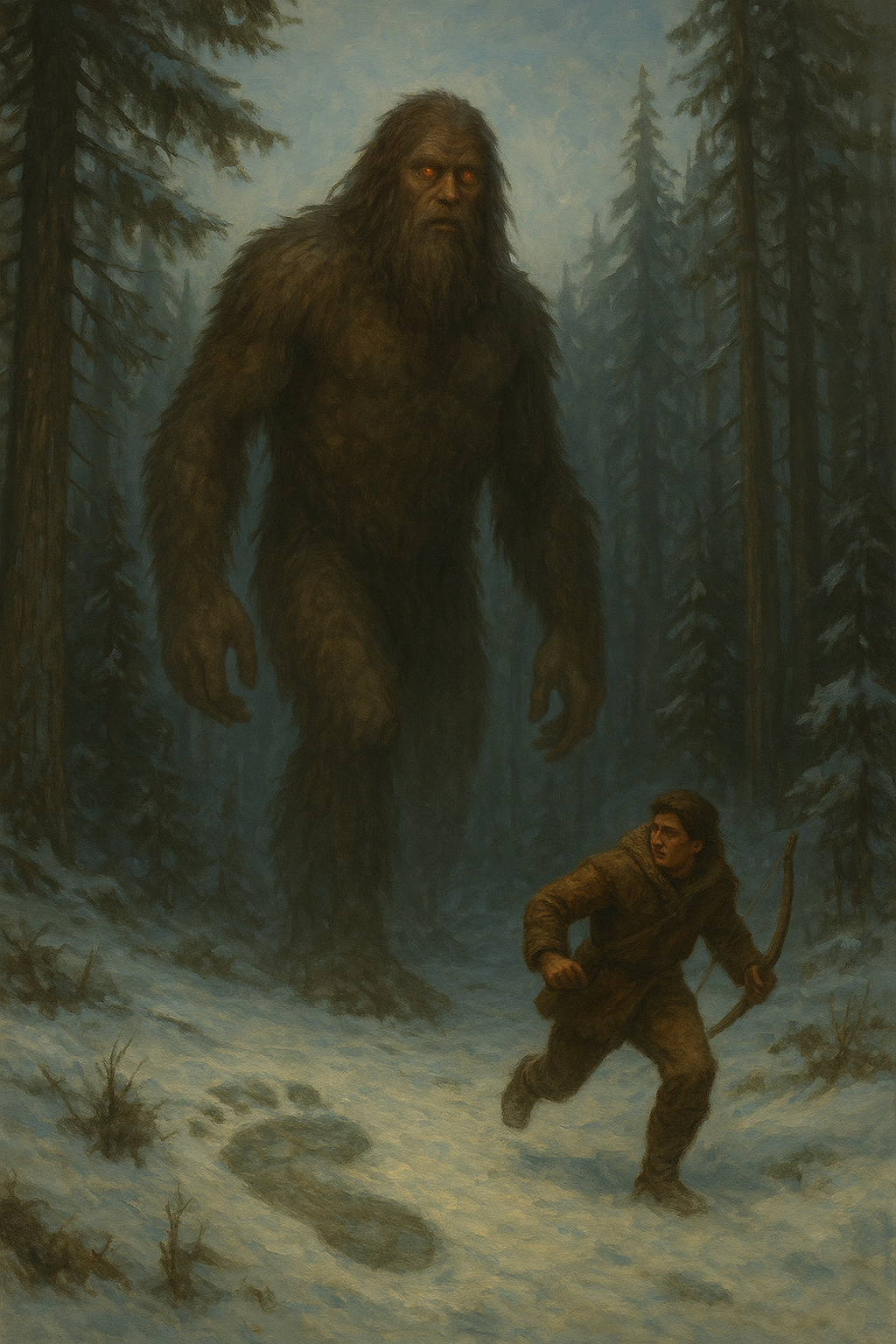

Among the many spirits that dwelled in the deep places of the forest was one not often seen, but always felt. A presence that moved through the shadows like smoke, leaving only traces of its passage. The people called him Sasq’ets, which in their ancient tongue meant “Wild Man of the Woods.” He was neither beast nor man, but something between, something older and deeper than either category could contain.

The elders told that Sasq’ets was born from the union of Earth and mist, created by the Great Spirit to serve as guardian of the wild places. His body was covered in thick brown hair that blended perfectly with the bark of ancient trees. He stood taller than the tallest man, with shoulders as broad as a bear’s and arms that could uproot small trees. His eyes were deep and knowing, holding the wisdom of countless seasons, and his voice, when he chose to use it, rumbled like distant thunder rolling through mountain valleys.

The old storytellers would gather the young ones around winter fires and speak of Sasq’ets with reverence and awe. They said he walked the forests to keep them in balance, to ensure that no creature took more than its share, that no hunter grew so proud as to forget the sacred relationship between life and death.

When hunters took more than they needed, killing for sport rather than survival, Sasq’ets would leave his great footprints by their lodges during the night. These prints, pressed deep into the earth, were a silent warning, a message written in the language of the land itself. The prints were enormous, far larger than any human foot, with five distinct toes that showed he walked upright like a man but belonged to the forest like the deer and elk.

If the hunters ignored this warning, if they continued their wasteful ways, they would find that their arrows had gone mysteriously dull, their spear points somehow bent, their traps sprung but empty. The animals would vanish from their usual hunting grounds as if spirited away, and the hunters would return to their families with empty hands and humbled hearts.

But when the people honored the land, when they took only what they needed and shared their kill with those who had less, when they gave thanks to the spirit of each animal that gave its life to feed them, then Sasq’ets would watch over their camps from the shadows. He would drive away the hungry wolves and prowling mountain lions. He would guide lost children back to the village. He would leave gifts near the lodges: sweet berries, healing herbs, or the shed antlers of great stags.

One particularly harsh winter, when snow lay deep upon the mountains and ice made the rivers silent, there lived a young hunter named Tahlah. He was strong and skilled, quick with his bow and fleet of foot. His arrows flew true, and his tracking abilities were admired by all the younger men of the village. But as his skill grew, so too did his pride.

Tahlah began to laugh at the old stories told by the elders. He would sit by the fire with a mocking smile playing at the corners of his mouth when they spoke of Sasq’ets and the sacred balance. “There is no spirit in the woods but my own two hands,” he would say boldly, flexing his strong arms. “No guardian but my own sharp eyes. These stories are for children who fear the dark.”

The elders shook their heads sadly and warned him that pride walks before a fall, that the forest has ears and the spirits have long memories. But Tahlah would not listen. He began to hunt not for need, but for the thrill of the kill itself. He would bring down three deer when his family needed only one. He would kill young elk for their tender meat and leave the tougher portions to rot. He left the bones scattered and dishonored, gave no thanks to the spirits of the animals who had died, and boasted loudly of his prowess.

One night, as fresh snow began to fall in thick, silent curtains and the wind howled like a lonely wolf, Tahlah saw the tracks of a large deer leading deep into the ancient cedar forest. Despite the late hour and the gathering storm, despite his wife’s pleas that he wait for morning, his pride drove him to follow. He wanted to prove once more that he was the greatest hunter in all the mountains.

He followed the trail as the snow fell heavier, covering his own tracks behind him. The forest grew darker and deeper around him, the cedars so tall they seemed to hold up the very sky. Then, gradually, Tahlah became aware that something had changed. The forest had grown still, too still. The wind had stopped its howling. The snow fell without sound. Even his own breathing seemed muffled, as if the forest itself was holding its breath.

Then, from deep within the shadows between the ancient trees, came the sound of footsteps. Slow, deliberate, heavy steps that made the frozen earth tremble. Each footfall sounded like a drum beat in the terrible silence.

Tahlah gripped his bow tighter, his heart beginning to pound. He turned in a slow circle, trying to locate the source of the sound. Then he saw it. A shape rose from the darkness before him, emerging from the shadows as if the night itself had taken form. It was taller than any man Tahlah had ever seen, broader than the largest warrior, its body covered in thick, dark hair that seemed to absorb what little light filtered through the snow-heavy trees.

The creature’s eyes caught the faint moonlight and glowed like embers in the darkness, ancient and knowing and filled with a power that made Tahlah’s legs turn weak beneath him. This was no bear, no elk, no natural creature of the forest. This was Sasq’ets, the Wild Man of the Woods, the guardian the elders had spoken of, the spirit Tahlah had mocked and dismissed.

Sasq’ets did not speak with words, for his language was older than human speech. But the wind itself seemed to carry his message, whispering through the trees and into Tahlah’s very soul: “You take without thanks. You hunt without heart. You have broken the sacred balance.”

Terror seized Tahlah completely. He dropped his bow into the snow and ran, crashing through the undergrowth like a panicked rabbit, his breath coming in ragged gasps, his heart threatening to burst from his chest. Behind him, he could hear the spirit following, those massive footsteps echoing through the mountains like thunder, like war drums, like the heartbeat of the earth itself.

All through that long, terrible night, Tahlah ran. Branches tore at his clothes and scratched his face. He stumbled over roots hidden beneath the snow and fell again and again, but fear drove him onward. The footsteps never seemed to grow closer, but they never faded either, always there behind him, relentless and patient.

When dawn finally came, painting the eastern sky in shades of pink and gold, Tahlah stumbled into the village, his legs barely able to hold him upright. He was trembling from head to foot, unable to speak, his eyes wide with the memory of what he had seen. The elders came quickly, wrapping him in warm furs and giving him hot tea, drawing the story from him slowly.

Then they went to examine his trail, and there in the frozen earth they found his footprints, small and frantic, showing his panicked flight through the forest. But beside his prints, pressed deep into the frozen ground, were the tracks of Sasq’ets. Each print was massive, three times the size of a human foot, showing five distinct toes and a stride that spoke of immense strength and purpose.

From that day forward, Tahlah was a changed man. The pride and arrogance that had filled him drained away like water from a broken pot. He hunted only what his family needed, and no more. Before each hunt, he would pray to the spirits and ask permission. After each kill, he would thank the animal for its sacrifice and honor every part of its body, using the meat for food, the hide for clothing, the bones for tools, the sinew for thread, wasting nothing.

He began to leave gifts in the forest as the elders had taught: a carved stick placed carefully beneath a cedar tree, a small fire built as an offering, a song sung in the old language to honor the guardian of the wild places. And sometimes, when he hunted in the deep woods, he would feel the presence watching him from the shadows, feel the weight of those ancient eyes upon him. But now there was no fear, only respect and gratitude.

The people said that Sasq’ets watched from afar, hidden by the mists and shadows, content that balance had been restored, that the proud young hunter had learned humility and respect. The great footprints were no longer a warning, but a blessing, a sign that the guardian still walked the forests, still kept watch over the Great Breathing Earth.

And so the legend lived on, passed from grandparents to grandchildren, from elder to young hunter, reminding all who heard it of the sacred relationship between humanity and the wild. When the mists drift low through the valleys and the tall pines whisper as if in breath, when the wind carries sounds that might be footsteps or might be something older, the people still say that Sasq’ets walks again through his domain.

He comes not to frighten, but to remind all who dwell upon the Earth that every life taken must be honored, every gift from the land repaid with gratitude and respect. He is the keeper of balance, the guardian of the ancient ways, the Wild Man of the Woods who ensures that the Great Breathing Earth continues to breathe, continues to live, continues to offer its gifts to those who approach with humble hearts.

Explore Native American beings, swamp creatures, and modern cryptid sightings across the country.

The Moral Lesson

This profound tale teaches us about the sacred responsibility that comes with taking from nature. Tahlah’s journey from prideful hunter to humble steward shows that true strength lies not in domination of the natural world, but in living in respectful balance with it. The story reminds us that every resource we take from the earth comes with an obligation to give thanks and to take only what we truly need. Sasq’ets represents the conscience of the wilderness, the reminder that we are not separate from nature but part of it, and that our actions have consequences that ripple through the web of life. The tale calls us to approach the natural world with reverence, gratitude, and humility.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Sasq’ets in this Native American folktale and what is his role?

A: Sasq’ets, meaning “Wild Man of the Woods,” is a guardian spirit described as neither beast nor man but something in between, born from the union of Earth and mist. His role is to maintain balance in the forest by ensuring hunters take only what they need and honor what they take. He serves as both protector of those who respect the land and a warning to those who abuse it.

Q2: What is the “Great Breathing Earth” and what does it represent?

A: The Great Breathing Earth is what the mountain people called the land, believing that every tree, stream, and stone carried a spirit and was alive. This concept represents the Native American worldview that nature is not merely a resource to be used, but a living, sacred entity deserving of respect. It reflects the interconnectedness of all things and the belief that the land itself is conscious and aware.

Q3: How does Sasq’ets warn hunters who take too much from the forest?

A: Sasq’ets first leaves his enormous footprints near the lodges of wasteful hunters as a silent warning. If they ignore this sign, their hunting tools mysteriously fail (arrows go dull, spear points bend), their traps spring empty, and the animals vanish from their usual grounds. These escalating consequences force hunters to recognize their violations of the sacred balance.

Q4: What was Tahlah’s mistake and how did he change?

A: Tahlah’s mistake was allowing pride to override respect for the sacred balance. He mocked the elders’ stories, hunted more than he needed, left meat to rot, and gave no thanks to the animals’ spirits. After his terrifying encounter with Sasq’ets, he transformed into a humble hunter who took only what was needed, honored every part of each animal, and left gifts in the forest as offerings of gratitude and respect.

Q5: What is the significance of the footprints in this folktale?

A: The massive footprints serve multiple symbolic purposes: they are physical proof of Sasq’ets’s existence, a warning system to wasteful hunters, and a way the spirit communicates without words. The footprints represent the tangible evidence that the spiritual world intersects with the physical, and that actions in the natural world are being observed and judged by forces greater than ourselves.

Q6: What Native American values and beliefs are reflected in this story?

A: The story embodies several core Native American values including respect for nature and all living things, the belief in spirits inhabiting the natural world, the importance of taking only what is needed (sustainable living), the practice of giving thanks and offerings for gifts received, the consequences of pride and disrespect, the wisdom of elders and traditional knowledge, and the concept of reciprocity that humans have obligations to the earth in exchange for its gifts. It reflects the worldview that humans are not masters of nature but participants in a sacred, balanced relationship with all creation.

Source: Native American folktale, United States