High in the mist-covered mountains where clouds cling to jagged peaks like tattered flags, and deep within the endless forests of North America, where ancient pines reach toward heaven and the air smells of cedar and damp earth, the grizzly bear walks with quiet authority, a creature both feared and revered, massive and magnificent, embodying the untamed spirit of wilderness itself.

Long ago, before settlements dotted the valleys and before roads carved their way through mountain passes, the elders of the land, those who had lived closest to the wild places and listened most carefully to their teachings, spoke of the Great Brown Guardian, a spirit of the wild who ruled the forest with strength tempered by wisdom. This was not the rule of a tyrant, but the governance of one who understood the delicate web that connected all living things.

Explore Native American beings, swamp creatures, and modern cryptid sightings across the country.

Wherever the grizzly roamed, balance followed in its wake like a faithful shadow. It was said by those who watched carefully that when the bear dug for roots with its long, curved claws, claws that could tear through logs and earth with equal ease, it opened the earth’s lungs, turning the soil and letting new life breathe. Insects found homes in the disturbed ground. Seeds that had lain dormant suddenly found themselves positioned to sprout. The very act of the bear’s feeding became an act of cultivation.

When it wandered through berry patches in late summer, its massive body brushing against bushes heavy with fruit, seeds scattered and clung to its thick, coarse fur, fur that could be silver-tipped like frost, or dark brown like river stones, or golden like autumn grass. As the bear traveled miles through its territory, these seeds would fall, carried far from their parent plants, ensuring the forest would bloom again next spring in places where berries had never grown before. The grizzly was not just a consumer but a planter, not just a taker but a giver.

But the grizzly’s world, for all its grandeur and beauty, was not one of ease or luxury. Harsh winters tested its endurance, sending it into dens carved beneath fallen trees or dug into hillsides, where it would sleep for months while snow piled deep outside and the temperature plunged to deadly cold. Before hibernation, the bear had to eat voraciously, gaining hundreds of pounds, transforming its body into a living storehouse of fat that would sustain it through the long, dreamless sleep.

Rivers demanded skill and timing, standing in rushing water, sometimes chest-deep, the grizzly had to watch with infinite patience for the silver flash of salmon fighting their way upstream, leaping waterfalls in their desperate journey to spawn. The bear’s timing had to be perfect, its strike swift and accurate, to catch the slippery fish mid-leap or to pin them against river stones. Not every attempt succeeded. Even apex predators knew hunger.

And though it stood as one of nature’s mightiest creatures, weighing up to eight hundred pounds or more, capable of running faster than a horse in short bursts, strong enough to drag an elk carcass up a steep mountainside even the grizzly must sometimes yield. Yield to hunger when prey proved scarce. Yield to cold when storms raged beyond even its considerable endurance. Yield to man’s encroaching shadow, as forests shrank and territories were divided by roads and settlements.

The she-bears, the mothers with their precious cubs, guarded their young with a fierceness that became legendary. A mother grizzly defending her cubs was nature’s most dangerous force, all hesitation vanished, all caution abandoned. She would charge threats many times her size, roaring with a sound that echoed through valleys, a primal warning that transcended language.

These mothers taught their cubs everything they needed to know to survive in a world both beautiful and brutal. They taught them to climb trees when danger approached, though adult grizzlies grew too large and heavy to climb themselves, the cubs needed this skill when threatened by predators or aggressive males. They taught them to dig, showing them, which roots were edible, where ground squirrels made their burrows, how to extract grubs from rotting logs.

Most importantly, they taught them to know the rhythm of the forest, when to hunt in the cool hours of dawn and dusk, when to hide during the heat of midday, when to begin the long feast before winter, when to seek out a den and surrender to sleep as the first snows began to fall. The cubs learned not just survival skills, but something deeper: respect. Respect for the water that fed the salmon and quenched their thirst. Respect for the wind that carried scent and warning. Respect for the intricate balance that gave the mountain its life predator and prey, plant and animal, earth and sky all woven together.

Today, though the wilderness grows smaller year by year, pressed back by human expansion like a tide slowly receding from shore, the grizzly endures. Its numbers are far fewer than they once were, its range a fraction of what existed when the elders first told their stories. But in the remaining wild places in the northern reaches of Montana and Wyoming, in the vast spaces of Alaska, in the protected reserves where humans have finally learned to set aside room for wildness, the bears continue their ancient patterns.

In the silver light of dawn, when mist rises from the water like spirits ascending, the grizzly can still be seen standing in a rushing river, water spraying around its massive frame as it waits with the patience of stone. Then, suddenly, explosive movement, a salmon caught mid-leap, water flying, the bear’s powerful jaws closing around its prize. The sight is primordial, unchanged for millennia, a window into a world that existed long before us and, if we are wise, will continue long after.

Its presence in these wild places reminds us of truths we often forget: that true power is not domination but harmony. That strength means protecting rather than destroying. That survival lies in taking only what is needed and living as part of something greater than oneself. The grizzly does not conquer the forest, it inhabits it, shapes it, serves it, and is served by it in return.

The tale of the grizzly bear is not just one of might and muscle, though it possesses both in abundance. It is a story of guardianship of being keeper rather than owner, protector rather than exploiter. It is the story of nature’s strength woven seamlessly with wisdom, power balanced with patience, ferocity tempered with understanding. It stands as a reminder that even the fiercest heart beats in rhythm with the land it calls home, and that our own wild hearts might remember, if we listen carefully enough, that we too are meant to be keepers of the wild, not its conquerors.

Click to read all American Cryptids & Monsters — creatures of mystery and fear said to inhabit America’s wild landscapes.

The Moral of the Story

This tale teaches us that true strength lies not in domination but in living harmoniously with one’s environment. The grizzly bear, despite being one of nature’s most powerful creatures, demonstrates that real power includes restraint, respect, and understanding one’s role in the larger ecosystem. The story emphasizes that we are all part of nature’s balance what we take must be balanced with what we give back, and guardianship is a greater responsibility than ownership. The grizzly shows us that survival depends not on conquering nature but on understanding and respecting it, taking only what we need, and recognizing that our strength means little if we destroy the very systems that sustain us.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What does the title “Great Brown Guardian” signify in this North American folktale?

A: The Great Brown Guardian represents the grizzly bear’s role as protector and maintainer of forest balance. It signifies that the bear doesn’t just inhabit the wilderness but actively guards and nurtures it, ensuring the ecosystem remains healthy through its natural behaviors.

Q2: How does the grizzly bear contribute to forest ecology in the story?

A: The grizzly contributes by digging and turning soil while foraging for roots, which aerates the earth and allows new growth. It also disperses berry seeds through its fur as it travels, planting new growth across its territory. Its salmon fishing returns nutrients from the ocean to the forest ecosystem.

Q3: What survival skills do mother grizzlies teach their cubs?

A: Mother grizzlies teach cubs to climb trees for safety, to dig for roots and grubs, to fish for salmon, and most importantly, to understand the forest’s rhythms knowing when to hunt, when to rest, and when to prepare for hibernation. They also teach respect for the natural balance.

Q4: What challenges does the grizzly face in its mountain home?

A: The grizzly faces harsh winters requiring hibernation, the difficulty of catching fast-moving salmon, periods of hunger when prey is scarce, and increasingly, the encroachment of human development that shrinks its wilderness habitat and fragments its territory.

Q5: What does the grizzly’s fishing technique symbolize in the story?

A: The grizzly standing patiently in the river waiting for salmon symbolizes the balance between power and patience, action and stillness. It demonstrates that even the mightiest creatures must work with nature’s timing rather than against it, and that success requires both strength and wisdom.

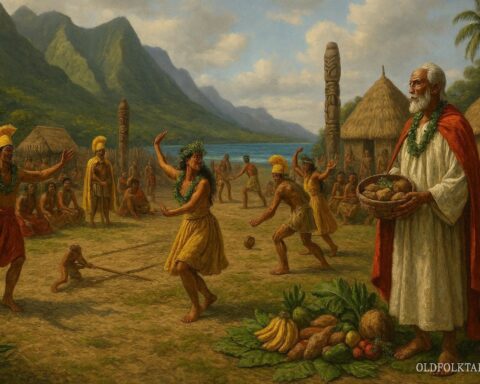

Q6: What is the cultural significance of the grizzly bear in Native American traditions?

A: In many Native American cultures, particularly among tribes of the Pacific Northwest and northern regions, the grizzly is revered as a powerful spiritual being representing strength, courage, and connection to the earth. It appears in creation stories and is honored as a teacher of balance, respect, and living in harmony with nature.

Cultural Origin

This tale originates from the mountainous regions of North America particularly the Rocky Mountains, Pacific Northwest, and Alaska where grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) have lived for thousands of years. The story reflects the deep respect held by indigenous peoples including the Tlingit, Haida, Blackfeet, and other tribes who shared their lands with these powerful animals. It weaves together Native American spiritual traditions that viewed the grizzly as sacred with ecological understanding of the bear’s crucial role in maintaining forest health and the sobering modern reality of habitat loss and conservation efforts to protect remaining wild spaces.