In the evenings, when work was finished and the heat of the day had faded, people gathered where voices carried best. Sometimes it was a kitchen, sometimes a courtyard, sometimes a campfire beyond the reach of town law. It was in these spaces that stories mattered more than documents. Here, history was not written. It was sung.

One name surfaced again and again, woven into melody and memory. Tiburcio Vásquez.

California had changed hands, but not hearts. The laws that arrived after annexation did not arrive gently. Land titles were questioned, language was dismissed, and families who had lived on the same soil for generations were told they no longer belonged. Courts moved quickly. Justice did not.

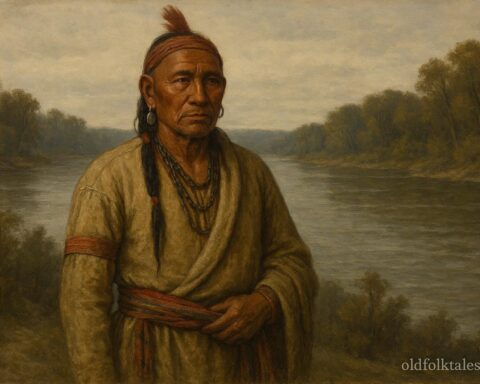

Tiburcio grew up watching that unraveling. His childhood was marked not by poverty, but by displacement. The loss was not sudden. It crept in through paperwork, new boundaries, and unfamiliar authority. By the time he was a young man, the world he had been raised to inherit no longer recognized him.

Explore the heart of America’s storytelling — from tall tales and tricksters to fireside family legends.

What followed was not inevitable, but it was understandable.

He did not begin as a legend. He began as a man who refused to accept erasure quietly. Each step he took away from settled life pulled him closer to the margins, and each act outside the law added weight to his name. But it was not his actions alone that shaped his legacy. It was the way people talked about them.

Ballads formed early, carried by traveling musicians and shared at gatherings where memory mattered more than fear. In these songs, Tiburcio Vásquez was not simplified. He was complicated, proud, defiant, flawed, and articulate. The verses lingered on his manners, his poetry, his refusal to abandon dignity even when hunted.

To some, the songs were warnings. They spoke of consequences, of paths that narrowed until no return was possible. To others, they were acts of preservation. Singing his name was a way of holding onto a history that official records ignored.

Authorities attempted to counter the narrative. Newspapers printed their own versions, stripped of context and heavy with condemnation. Yet those accounts rarely traveled beyond town limits. Songs crossed borders more easily than ink.

Tiburcio himself understood this divide. Witnesses later recalled that he paid attention to how he was spoken of. He quoted poetry. He corrected those who misrepresented him. In doing so, he participated in the shaping of his own legend, knowing full well that once captured, his voice would no longer guide the story.

As his reputation spread, fear and admiration grew side by side. Some communities shielded him, not because they endorsed violence, but because they recognized the injustice that had shaped him. Others refused, wary of reprisal. The ballads reflected this tension. No two were exactly the same.

In some verses, Tiburcio stood as a defender of the wronged. In others, he was a man consumed by pride. The truth mattered less than what people needed to express. Folklore does not exist to resolve contradictions. It exists to hold them.

When he was finally captured, there was no celebration in the songs. There was a quiet shift. The verses slowed. The tone darkened. His execution did not end the story. It anchored it.

Afterward, the ballads changed again. They moved away from events and toward meaning. Children learned his name not as instruction, but as context. Elders explained why the songs existed at all. They spoke of broken treaties, lost land, and the cost of silence.

Over time, Tiburcio Vásquez became less a man and more a symbol. His flaws were acknowledged. His choices debated. But his presence in folklore endured because he represented a moment when identity was threatened and song became defense.

Today, scholars analyze the ballads for structure and theme. Communities still sing them for memory. The difference matters.

In the space between history and legend, Tiburcio Vásquez remains. Not redeemed. Not erased. Remembered.

Click now to read all American Legends — heroic tales where truth and imagination meet, defining the American spirit.

Moral Lesson

When people are denied justice, storytelling becomes a way to preserve truth, identity, and cultural dignity.

Knowledge Check

- Why did ballads become central to Tiburcio Vásquez’s legacy?

Answer: They allowed communities to preserve memory outside official records - What broader historical change shaped the conflict in his story?

Answer: The annexation of California and loss of land for Californios - How did authorities attempt to control his narrative?

Answer: Through newspapers and legal condemnation - Why did communities continue singing about him after his death?

Answer: To preserve cultural history and shared experience - How did the ballads differ from official accounts?

Answer: They included context, emotion, and cultural meaning - What does his legend represent beyond his actions?

Answer: Resistance to cultural erasure

Source

Adapted from California State University folklore ballad archives

Cultural Origin

Californio and Mexican American communities