Black Hawk did not first become a leader on a battlefield. He became one through memory. As a boy among the Sauk people, he learned the shape of the land before he learned the shape of words. Rivers were not borders. Hills were not obstacles. The earth itself was a record of agreements made between generations. Cornfields were planted where ancestors had planted them. Burial grounds rested where spirits had chosen to remain. To know these places was to know who you were.

By the time Black Hawk reached adulthood, the land he knew was already being renamed. Treaties were spoken of in distant towns, written in languages his people did not read, and agreed upon by leaders who did not hold full authority within the Sauk nation. One such treaty, signed in 1804, claimed that the Sauk and Meskwaki had sold millions of acres east of the Mississippi River. Black Hawk never accepted it. He insisted the land had never truly been given away because the people had never consented.

For decades, tension grew quietly. American settlers arrived steadily, building cabins on fields where Sauk families still planted corn. Fences cut across hunting paths. Graves were disturbed. Each act felt small to those arriving, but to Black Hawk, they were warnings. He believed land was not property but responsibility. Losing it meant losing memory, law, and identity all at once.

Discover African American wisdom, Native American spirit stories, and the humor of early pioneers in American Folktales.

Black Hawk was not opposed to peace. He had fought alongside the British during earlier conflicts and understood the cost of war. But he also believed that leaving the homeland without consensus would erase the Sauk people as surely as violence would. When government agents demanded removal west of the Mississippi River, Black Hawk resisted not as a conqueror, but as a guardian.

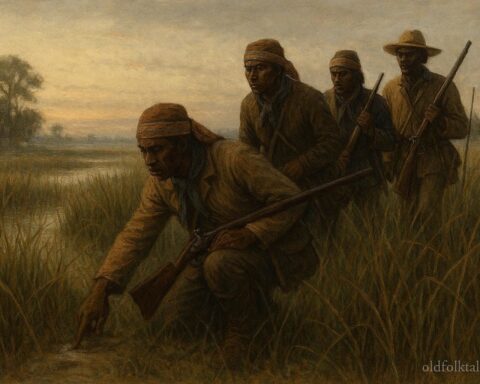

In 1832, after years of displacement pressure, Black Hawk led a group of Sauk, Meskwaki, and allied families back across the Mississippi to their ancestral village at Saukenuk. Many were women, children, and elders. They returned to plant crops, not to fight. Still, their presence was treated as an invasion. Militia forces mobilized. Negotiations failed. Fear spread faster than truth.

What followed became known as the Black Hawk War, though Black Hawk never sought a war bearing his name. Skirmishes broke out between militia and Indigenous groups. Misunderstandings escalated into violence. The Sauk people were pushed further north, pursued relentlessly. Hunger, exhaustion, and loss followed them. Black Hawk watched families fall apart under pressure that did not come from battle alone, but from displacement itself.

As the conflict dragged on, Black Hawk’s role shifted. He became less a commander and more a witness. He tried repeatedly to surrender, to explain that his people sought return, not conquest. But the machinery of expansion had no pause built into it. The war ended with devastating loss for the Sauk and Meskwaki. Survivors were forced west. Saukenuk was destroyed.

Black Hawk was captured and imprisoned. Later, he was taken east, displayed in cities as a defeated enemy. Crowds stared at him, expecting savagery, but encountered dignity instead. He spoke calmly. He did not beg. He told his story in his own words, later recorded as an autobiography. In it, he did not claim victory. He claimed truth.

What made Black Hawk a legend was not triumph, but refusal to forget. He refused to pretend the land was empty. He refused to accept that memory could be erased by paper. Even in defeat, he insisted on being remembered as a man who stood where he belonged.

After his release, Black Hawk lived quietly, no longer a war leader but still a symbol. His presence reminded both Indigenous and settler communities that removal did not mean consent, and silence did not mean surrender. Long after his death, his name remained tied to the Mississippi Valley not as a conqueror’s mark, but as a reminder that resistance can take the form of memory.

Today, Black Hawk’s story endures because it speaks to a deeper truth about leadership. He did not fight for power. He fought for continuity. He believed land carried obligation, not ownership. His legacy lives not only in history books, but in the ongoing efforts of the Sauk and Meskwaki people to preserve language, culture, and homeland connections.

Black Hawk stands among American folk heroes not because he won, but because he refused to disappear.

Click now to read all American Legends — heroic tales where truth and imagination meet, defining the American spirit.

Moral Lesson

True leadership is not measured by victory or recognition, but by the courage to defend memory, responsibility, and belonging even when the outcome is uncertain.

Knowledge Check

1 What belief did Black Hawk hold about land ownership?

Answer: He believed land was a shared responsibility tied to ancestors and future generations, not property to be sold

2 Why did Black Hawk reject the 1804 treaty?

Answer: He believed it was signed without proper consent from the Sauk people

3 What was Black Hawk’s main goal when crossing the Mississippi in 1832?

Answer: To return peacefully to ancestral lands and plant crops

4 Why did the conflict escalate into war?

Answer: Fear, misunderstandings, and pressure from settlers and militia forces

5 How did Black Hawk respond to imprisonment and public display?

Answer: He remained dignified and told his story in his own words

6 Why is Black Hawk remembered as a folk hero today?

Answer: For defending land, memory, and identity despite defeat

Source

Adapted from Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian historical folklore collections

Cultural Origin

Sauk and Meskwaki peoples, Midwest United States