Long ago, when the coquí frogs still sang their ancient songs loudly through the tropical night and the moon cast silver light across the tops of the mighty ceiba trees that stood like silent guardians of the island, there was a small village nestled in the misty hills of Puerto Rico called San Isidro del Monte. The name meant “Saint Isidore of the Mountain,” and it was a humble place, far from the coastal cities, where life moved to the slower rhythm of the seasons and the soil.

The people of San Isidro del Monte were simple farmers who worked the red clay earth with their hands, just as their parents and grandparents had done before them. They tended their goats and chickens with care, grew plantains and yuca in neat rows on the hillsides, and lived in modest homes with corrugated metal roofs that sang when the rain fell. They trusted in God and the saints, yes, but they also remembered, at least some of them did, that the old spirits of the island spirits that had been here long before the Spanish came, before the churches were built still watched from the shadows of the forest and the caves in the limestone hills.

Click now to read all American Legends — heroic tales where truth and imagination meet, defining the American spirit.

Life was hard but predictable, peaceful but modest. The villagers knew each other’s names and histories, shared their harvest during times of plenty, and helped one another through the lean times. It was a good life, or good enough.

But one summer, when the heat lay heavy on the land and the air grew thick and still before the evening rains, something strange began to happen in San Isidro del Monte.

It started with a single goat belonging to Don Rafael, an old herdsman whose weathered face told the story of sixty years under the Caribbean sun. One morning, as the first light was just beginning to paint the eastern sky pink and gold, Don Rafael went out to check on his small herd as he did every day. There, lying in the dusty pen, was one of his best goats, a strong young female that had just given birth to twin kids the month before.

She lay cold and stiff in the dirt, her eyes open but seeing nothing, her body pale and somehow deflated, as if all the life had been drained from her. Don Rafael knelt beside her, his knees creaking with age, and examined her carefully. There was no blood on the ground, no claw marks raking her sides, no teeth marks on her throat, no signs that she had struggled or fought for her life. The only mark on her entire body was two small punctures on her neck, neat and precise, as if something sharp as a needle had pierced the skin.

Don Rafael had raised goats for fifty years and had never seen anything like it. He carried the dead animal to show the other villagers, and they gathered around it in the central plaza, murmuring and speculating. Perhaps it had been a stray dog that had wandered up from the valley? Perhaps a particularly large bat, feeding on blood as some bats did? The theories flew back and forth, but none quite explained the strange, bloodless death.

But theories became irrelevant when another goat was found the next morning. And then a chicken the morning after that. Then three more goats from Pedro Martínez’s farm on the next ridge over, all discovered in the same horrifying condition, drained of blood, bearing only those two mysterious puncture wounds on their necks.

Fear began to creep into San Isidro del Monte like a fog rolling in from the sea, silent and suffocating. The farmers, who had always left their animals out at night under the stars, now began locking them in barns and coops after sunset. But still the deaths continued, as if locked doors and wooden walls meant nothing to whatever was hunting in the darkness.

The villagers went to Father Domingo, the parish priest, a kind man with gray hair and a gentle manner who had served their community for twenty years. He listened to their fears with concern, blessed containers of holy water, and accompanied the farmers to their fields where he sprinkled the blessed water on the ground and on the animals, speaking prayers of protection in Latin and Spanish. He told the frightened people to have faith, to trust in God’s protection, to pray the rosary each evening.

But faith, as strong as it was, could not seem to keep the livestock alive. The deaths continued with terrifying regularity, always occurring during the night, always leaving the victims completely drained of blood, and always happening without a single sound, no barking of dogs, no frightened cries from the animals, nothing but silence and death.

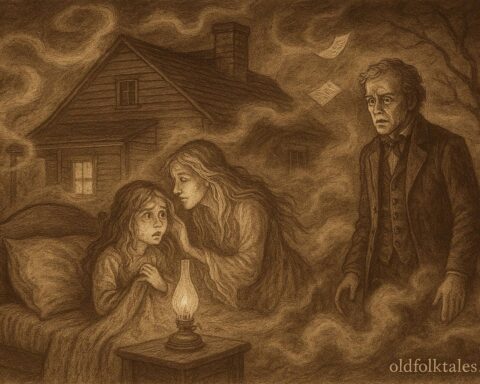

One muggy night, when the air was so thick you could almost taste it and heat lightning flickered on the horizon, a young woman named María Torres was lying awake in her small house on the very edge of the village where the cultivated fields gave way to wild forest. She lived there with her parents and younger brother Luis, and her bedroom window looked out over their modest goat pen.

Unable to sleep in the oppressive heat, María lay listening to the night sounds: the endless chirping of the coquí frogs, the rustle of palm fronds in the slight breeze, the distant rumble of thunder. Then she heard something different, a strange noise just outside her window that made her blood run cold.

It was not the cry of a dog, nor the deep croak of a frog, nor the hiss of wind through the coconut palms. It was something wet and organic, a rasping sound like breathing mixed with a low growl, the sound a sick animal might make, but somehow more intelligent, more purposeful.

Heart pounding, María crept to the window and peered carefully through the wooden shutters. At first, she saw nothing but shadows in the moonlight. Then movement caught her eye, something was among the goats in the pen below.

At first glance, she thought it might be a man, crouched low as if trying to hide. But then the creature straightened up, and María’s breath caught in her throat. Under the pale light of the three-quarter moon, she could see its shape clearly, and it was like nothing she had ever seen or imagined.

It was roughly the size of a large dog or a small person, but its proportions were all wrong, nightmarish. Its body was thin and bony, with long, spindly arms and legs that seemed to bend at impossible angles, as if the joints worked backwards. Its skin was gray and rough, like old leather left too long in the sun, stretched tight over protruding ribs and sharp bones. Along its spine ran a row of sharp spines or quills, like those of a porcupine but longer and more wicked-looking. And its eyes dear God, its eyes glowed with a terrible red light, like burning embers pulled from a fire, filled with an intelligence that was neither human nor animal but something in between.

As María watched in frozen horror, the creature bent over one of the goats. She could see its head moving, hear a soft slurping sound, and when it rose again a moment later, dark liquid, blood-dripped from its mouth and ran down its gray chin.

María’s scream tore through the night, high and piercing, shattering the terrible silence.

The creature’s head snapped toward her window with inhuman speed. Those burning red eyes locked onto hers through the shutters, and for a single, eternal heartbeat, the entire world seemed to go still. María could not move, could not breathe, pinned by that alien gaze like a butterfly on a collector’s board.

Then the moment broke. The creature opened its mouth revealing rows of needle-sharp teeth-stained dark with blood and let out a hiss that sounded almost like words, like cursing in a language no human throat should be able to form. With one powerful leap, it sprang into the darkness, moving with terrible speed on those backwards-bending legs, and vanished into the forest with a rustling of leaves and snapping of branches.

By the time María’s parents and brother reached her room, drawn by her scream, the creature was gone. But by morning, when the gray light of dawn crept over the hills, the villagers had gathered outside the Torres home. They found the goat lying in the pen, lifeless and pale as wax, with the now-familiar twin puncture marks on its neck. And they found something else, a trail of clawed footprints leading from the pen toward the forest, prints unlike any animal native to Puerto Rico. The prints seemed to shimmer faintly in the early light, as if they had been scorched into the earth by something burning hot.

María told her story to the gathered crowd, her voice shaking, her hands trembling as she described the creature she had seen. Some believed her immediately. Others thought fear and darkness had played tricks on her eyes. But everyone felt the weight of dread settling more heavily on the village.

That night, the elders of San Isidro del Monte gathered by a fire in the plaza. These were the oldest residents, men and women who remembered the stories their own grandparents had told them, who still knew some of the old ways that were slowly being forgotten. Among them was Doña Isabela, ancient and bent but with eyes still sharp as a hawk’s. She had been born in San Isidro and had never left, had seen nearly ninety years pass like water flowing in the streams.

When the others had finished their speculation and arguing, Doña Isabela spoke, and her voice, though quiet, commanded attention.

“This is not the work of a wolf,” she said slowly, “nor a demon brought from Europe in the ships of the conquistadores. This is our own curse, born of our own forgetting. Long ago, before the churches with their bells and crosses were built on every hill, the spirits of this land guarded our people. The spirits of the ceiba trees, the caves, the rivers, the mountains they watched over us, and in return, we gave them offerings and respect. We listened to the whispers of the forest and honored what we could not see.”

She paused, staring into the fire, its light dancing across her wrinkled face.

“But the young have forgotten to offer thanks. We have stopped listening. We build our houses and farms and churches, and we think we have tamed the island, think we own it. We take and take and never give back. Now something else listens in our place. Something that remembers when we do not.”

From that night onward, as Doña Isabela’s words spread through San Isidro, no one dared leave their homes after the sun set. Mothers drew crosses of salt on their doorsteps, ancient protection against evil. Fathers hung braids of garlic and rosaries blessed by Father Domingo over the windows and doors. Children were forbidden to play outside after dark. The village that had once been lively with evening gatherings and music now fell silent the moment twilight descended.

Yet still, despite all precautions, the deaths came. Chickens disappeared from locked coops, found the next morning drained and cold. A pig, kept in a sturdy pen, met the same fate. Even a horse belonging to the wealthiest farmer in the valley was found dead, all its blood gone, with only those two precise holes at the neck.

The people of San Isidro began calling the creature el chupacabra “the goat sucker” and the name spread to neighboring villages, then to the towns, carried on the lips of frightened farmers who came to market with their remaining livestock.

Weeks passed in this way, with fear becoming a constant shadow over the village, as much a part of daily life as the heat and the rain. Then one evening, as summer was beginning to fade toward autumn, a massive storm rolled across the hills from the ocean. Thunder shook the houses until the dishes rattled in their cupboards, and rain pounded the red clay earth so hard it bounced back up, turning the roads to rivers of mud.

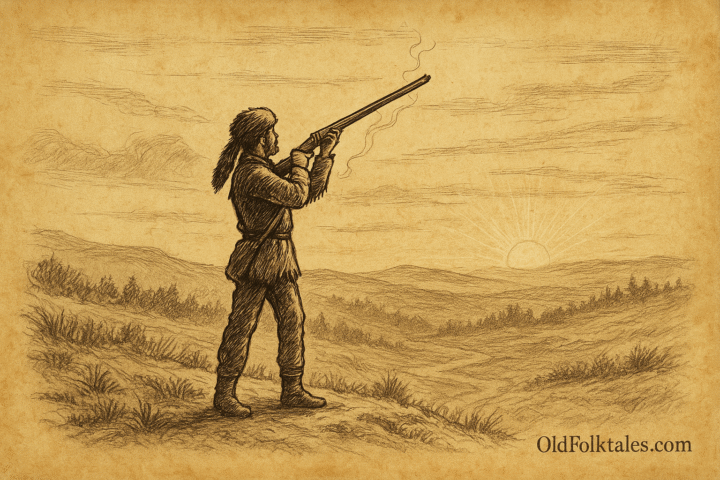

In that storm, a young man named Luis Torres, María’s younger brother, though at nineteen he stood taller and stronger than most men in the village took up his father’s machete, the blade sharp and gleaming, and swore before his frightened family that he would face the beast himself.

“Better I die fighting like a man,” he said, his jaw set with determination, “than cowering in the dark like a frightened child. This thing has taken enough from us. Tonight, it ends.”

His mother wept and begged him not to go. His father tried to reason with him. But Luis’s mind was set. He had seen his sister’s terror, had watched his father’s livelihood slowly destroyed, had felt the fear that gripped their home like a strangling vine. Enough was enough.

He went out into the storm with only a lantern in one hand and his courage in his heart, the machete hanging at his side. The rain soaked him instantly, and the wind tried to tear the lantern from his grip. Lightning flashed across the sky in jagged forks of white fire, and in one of those brilliant flashes, Luis saw it.

Perched upon a large rock near the goat pen, as still as a gargoyle on a cathedral, was the Chupacabra. Its spines were slick with rain, its gray skin glistening wetly, and its mouth was red with fresh blood, glistening in the lightning’s glare.

Luis shouted a prayer his grandmother had taught him, words in Spanish calling on the protection of San Miguel, the warrior archangel. He raised his machete high, the blade catching the lightning’s reflection.

The creature shrieked, a sound that pierced through the thunder and the rain, a sound that echoed through the valley and made every dog for miles around howl in response. It was a sound of rage and hunger and something else, something that might have been recognition or challenge.

The Chupacabra leaped from its rock, claws extended like daggers, moving with terrifying speed. But Luis was young and quick, and fury gave him strength. He swung the machete with all the power in his body, and the blade connected with the creature’s outstretched arm.

There was a sound like metal striking stone, and a burst of black blood, thick as tar, sprayed from the wound. Where the blood hit the ground, it hissed and steamed despite the rain, as if it were acid or something burning hot.

The creature stumbled back, clutching its wounded arm, and for the first time Luis saw fear in those glowing red eyes. It glared at him with fury and pain, its mouth open in a silent snarl. Then, with one powerful leap that defied the laws of nature, it sprang into the air and vanished into the dense jungle that pressed close around the village, leaving behind only its echoing shriek, fading gradually into the sound of thunder.

Luis stood in the pounding rain, his chest heaving, his arm bleeding from where the creature’s claws had raked him in that brief, terrible combat. But he was alive. He had faced the Chupacabra and survived.

He returned to the village as dawn was breaking, the storm spent, the world washed clean. His family embraced him, weeping with relief. The other villagers emerged cautiously from their homes and gathered to hear his tale. When the sun was fully up and courage had returned with the light, a group of men armed with machetes and clubs went to search the forest, following the trail of that strange black blood.

The trail led them deep into the limestone hills, to a cave hidden behind a curtain of vines and ferns. The mouth of the cave was narrow and dark, and the men had to light torches to enter. Inside, the cave opened into a larger chamber, and there they found bones, piles of bones from goats and chickens and other animals, picked clean and dry, brittle as ash. But of the creature itself, there was no sign. The cave was empty.

After that night, no more animals were killed in San Isidro del Monte. The Chupacabra was gone, fled to some other valley, perhaps, or dead from its wound, or simply sleeping in some deeper cave, waiting. Waiting for the people to forget once more the old ways, the offerings, the respect owed to the spirits of the land.

And so the tale passed from mouth to mouth, from grandmother to grandchild, from the misty hills of Puerto Rico to the dry deserts of Texas and Mexico, changing shape as it traveled, growing and adapting, just as the creature itself was said to be able to change its form.

Even now, decades later, when the moon is full and fat in the sky and the goats grow restless in their pens for no reason anyone can name, the old people of San Isidro del Monte whisper to each other: “Keep your lights burning bright through the night. Remember to thank the land for what it gives. For when the island grows careless and the people forget their gratitude, when they take without giving back, the Chupacabra walks again hunting not merely for hunger, but to remind us of what we have forgotten, of the debts we owe, of the balance that must be maintained between the human world and the world of spirits.”

Explore how American legends shaped the nation — from frontier heroes to Revolutionary War tales.

The Moral Lesson

This haunting tale teaches us about the importance of respecting the natural world and maintaining the sacred balance between taking and giving. The Chupacabra appears not as random evil, but as a consequence of the village’s forgetting their failure to honor the old spirits of the land and show gratitude for what they receive. The story reminds us that nature demands respect and reciprocity, and that when we take from the earth without giving thanks or maintaining balance, we upset forces larger than ourselves. It also celebrates courage in the face of fear, as Luis demonstrates that sometimes we must stand and fight rather than cower, even when facing the unknown. Most profoundly, the tale warns that some lessons must be relearned by each generation, lest we repeat the mistakes of forgetting what our ancestors knew.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What is el Chupacabra and how is it described in this American folktale?

A: El Chupacabra, meaning “the goat sucker,” is a mysterious creature that drains the blood from livestock. It is described as roughly the size of a large dog, with a thin, bony body, gray leathery skin stretched over protruding ribs, long arms and legs that bend at wrong angles, sharp spines running down its back, needle-sharp teeth, and glowing red eyes like burning embers. It leaves only two precise puncture marks on its victims’ necks and drains them completely of blood.

Q2: Who is Doña Isabela and what explanation does she give for the creature’s appearance?

A: Doña Isabela is the eldest resident of San Isidro del Monte, nearly ninety years old and keeper of the old stories and traditions. She explains that the Chupacabra is not a European demon but “our own curse” a consequence of the villagers forgetting to honor the old spirits of the land. She says that before the churches came, people gave offerings and respect to the spirits of the trees, caves, and mountains, but the young have forgotten these practices, and now something else has taken the place of those protective spirits.

Q3: How does María Torres first encounter the Chupacabra?

A: María Torres hears a strange, wet rasping sound outside her window one night breathing mixed with a growl. Looking through her shutters, she sees a creature among the goats that appears human at first but then stands to reveal its true, horrifying form. She watches it drain blood from a goat, and when she screams, the creature turns its glowing red eyes toward her, hisses in what sounds almost like words, and then leaps away into the forest with supernatural speed.

Q4: Who is Luis Torres and how does he confront the Chupacabra?

A: Luis Torres is María’s nineteen-year-old brother who refuses to live in fear any longer. During a massive storm, he takes his father’s machete and goes out to face the creature. When he finds it perched on a rock, he shouts a prayer to San Miguel and attacks with his machete. He manages to wound the creature’s arm, causing black blood to spray out that hisses when it hits the ground. Though he is scratched by the creature’s claws, Luis survives the encounter and the creature flees into the jungle.

Q5: What do the villagers find when they track the creature to its lair?

A: Following a trail of the creature’s strange black blood, the villagers find a hidden cave in the limestone hills. Inside the cave, they discover piles of bones from goats, chickens, and other animals all picked completely clean and dry as ash. However, the Chupacabra itself is gone, having either fled, died from its wounds, or gone deeper into hiding. After this discovery, no more animals are killed in the village.

Q6: What cultural and spiritual elements are present in this American folktale from Puerto Rico?

A: The story features the ceiba tree (sacred in Taíno indigenous tradition), coquí frogs (unique to Puerto Rico), traditional farming life in the mountain villages, the blending of Catholic faith (Father Domingo, rosaries, prayers to San Miguel) with indigenous spiritual beliefs about land spirits, the Spanish language terms and names, the limestone hill caves common to Puerto Rico’s geography, and the concept of maintaining balance with nature through offerings and gratitude. The tale reflects the syncretism of indigenous Taíno, Spanish Catholic, and African Caribbean spiritual traditions that characterize this region of American folklore.

Source: American folktale from Puerto Rico