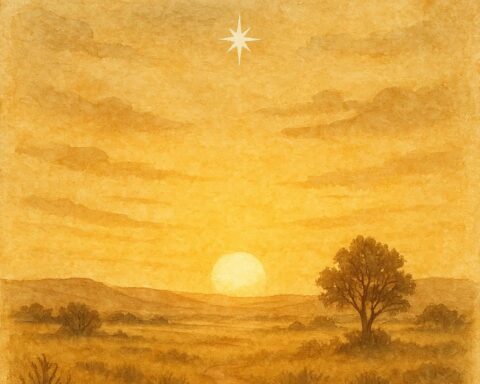

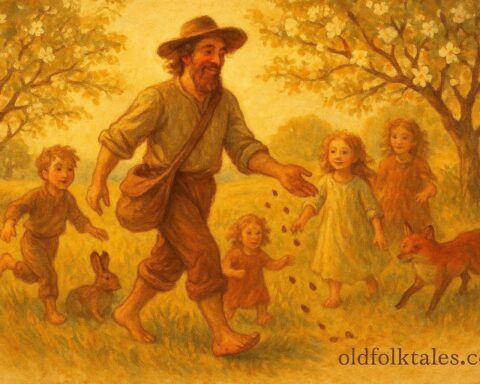

When the world was young, the skies stretched endlessly over shimmering waters. The land had vanished beneath a vast flood that swallowed mountains, forests, and plains. The only living beings left adrift upon the endless waves were Nanabozho, the Great Hare and powerful culture hero of the Ojibwe people, and a few loyal animal companions, Otter, Beaver, Loon, and Muskrat.

Nanabozho, weary and saddened by the destruction of the world, floated upon a log, gazing out across the empty water. The winds whispered sorrow through the mist, and the Great Hare’s heart ached for the earth that once thrived with life. “All that once was has been swept away,” he said softly. “But perhaps, if we can find even a little piece of the old earth, we might begin anew.”

Click to explore all American Ghost Stories — haunting legends of spirits, lost souls, and mysterious places across the U.S.

The animals gathered around him, their fur slick with water, their eyes filled with determination. Nanabozho looked at each one and said, “If one of you can dive deep beneath the flood and bring up some earth from the bottom, I will use it to create the land again. The world may yet be reborn.”

The challenge was great. None knew how far the depths went or what dangers lay below, but they were loyal to Nanabozho and the spirit of creation. One by one, they prepared to dive.

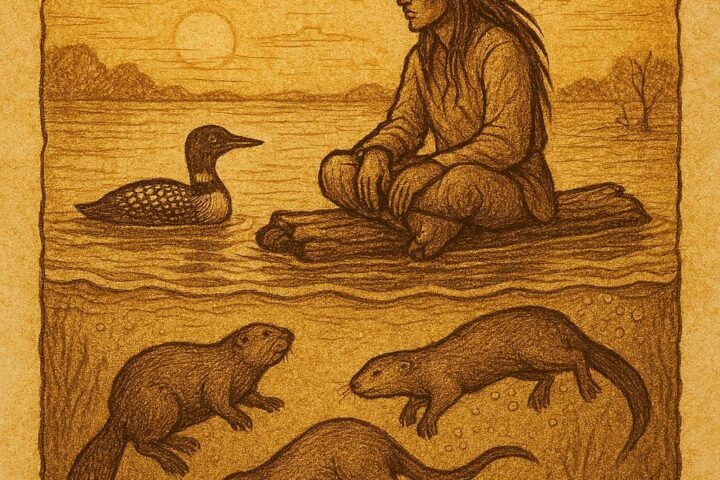

First went the Loon, known for its skill in swimming and its haunting call across northern lakes. With a sharp cry, the Loon plunged into the dark water, his wings folded tight. Down he went, deeper and deeper, until the surface grew still. Nanabozho and the others waited. Bubbles rose, but no bird returned. Finally, the Loon burst through the water, gasping, but his claws were empty. He shook his feathers and bowed his head. “It is too deep,” he whispered.

Next, the Beaver volunteered. Strong and steady, the Beaver slapped his tail upon the water and dove. His powerful legs kicked hard, driving him downward into the cold black depths. The animals watched for what seemed like hours, the ripples fading. At last, the Beaver reappeared, panting and exhausted. “I reached far,” he said between breaths, “but no bottom could I touch.”

Then the Otter tried. Swift and graceful, she dove with ease, her sleek body cutting through the waves. Nanabozho and the others waited anxiously. The Otter stayed below longer than the others, and for a moment, hope flickered in Nanabozho’s heart. But when she emerged, she too carried nothing. “The deep holds no end,” she sighed, shaking her fur.

Silence fell. The flood stretched endlessly around them. Then, from the edge of the group, the small voice of the Muskrat spoke up. “Let me try,” he said quietly. The others turned to look at him, tiny, unassuming, and frail compared to the mighty Beaver and Otter. Nanabozho gazed kindly at the little creature. “You are brave, little one,” he said gently, “but the task may be too great.”

Still, Muskrat insisted. “I may be small,” he said, “but I will do my best.” And before anyone could stop him, he took a deep breath and dove beneath the water.

Down he went, past the cool shallows, into the cold, heavy darkness where light could not follow. His small paws paddled, his lungs strained, and the weight of the water pressed against his chest. Yet he did not give up. The others waited for him at the surface, their hearts heavy with worry. Time passed, too much time.

At last, something stirred. The animals saw a still shape rise through the waves. It was Muskrat, his body limp, his breathing gone. Nanabozho gently lifted him from the water, sorrow filling his heart. But as he looked closer, he saw that in the Muskrat’s tiny paw was a small clump of mud.

“Brave little one,” whispered Nanabozho, his voice trembling with emotion. “You have done what none of us could.”

Carefully, Nanabozho took the bit of earth from Muskrat’s paw and placed it upon the surface of the water. He blew upon it softly, once, twice, three times. The mud began to spread and swell, rippling outward in every direction. It grew into an island, then a vast stretch of land, mountains, valleys, forests, and plains. The world had been reborn.

When the wind settled and the waters calmed, Nanabozho looked around the new earth. He spoke to the animals: “Let all remember the Muskrat’s courage. Though he was the smallest among us, his heart was the greatest. From his sacrifice, the world has life again.”

And so it was that the Ojibwe people tell how the humble Muskrat, through bravery and perseverance, brought the land back from the depths of the flood. His story reminds all that greatness does not come from strength or size, but from the will to try when hope seems lost.

Explore the heart of America’s storytelling — from tall tales and tricksters to fireside family legends.

Moral Lesson

This Ojibwe folktale teaches that true strength lies in humility and courage. Even the smallest creature can change the world through determination and faith. Every being, no matter how modest, has a purpose in the circle of life.

Knowledge Check

1. Who is Nanabozho in the story?

Nanabozho is the Great Hare, a culture hero in Ojibwe mythology, who survives the flood and recreates the earth.

2. What challenge did Nanabozho give the animals?

He asked them to dive to the bottom of the flood and bring up some earth to rebuild the world.

3. Which animals tried before Muskrat?

The Loon, Beaver, and Otter each tried but failed to reach the bottom.

4. What lesson does Muskrat’s success teach?

That courage and perseverance, not size or strength, determine true greatness.

5. How did Nanabozho recreate the world?

He took the bit of mud Muskrat brought and blew upon it, causing the land to grow and form the earth anew.

6. What cultural value does the story reflect?

It reflects the Ojibwe belief in balance, humility, and the sacred connection between animals, humans, and creation.

Source: Adapted from American Indian Fairy Tales by W. T. Larned, based on Henry R. Schoolcraft (1917), Project Gutenberg.

Cultural Origin: Ojibwe (Chippewa) folklore, North America.