Long ago, when the world was quieter and the forests of the American South still whispered the voices of Africa’s old stories, a traveler walked a lonely road. The sun hung low in the sky, and the air was heavy with the hum of insects and the scent of wild grass. The man had been walking for hours, his feet dusty and his mind wandering from hunger and boredom.

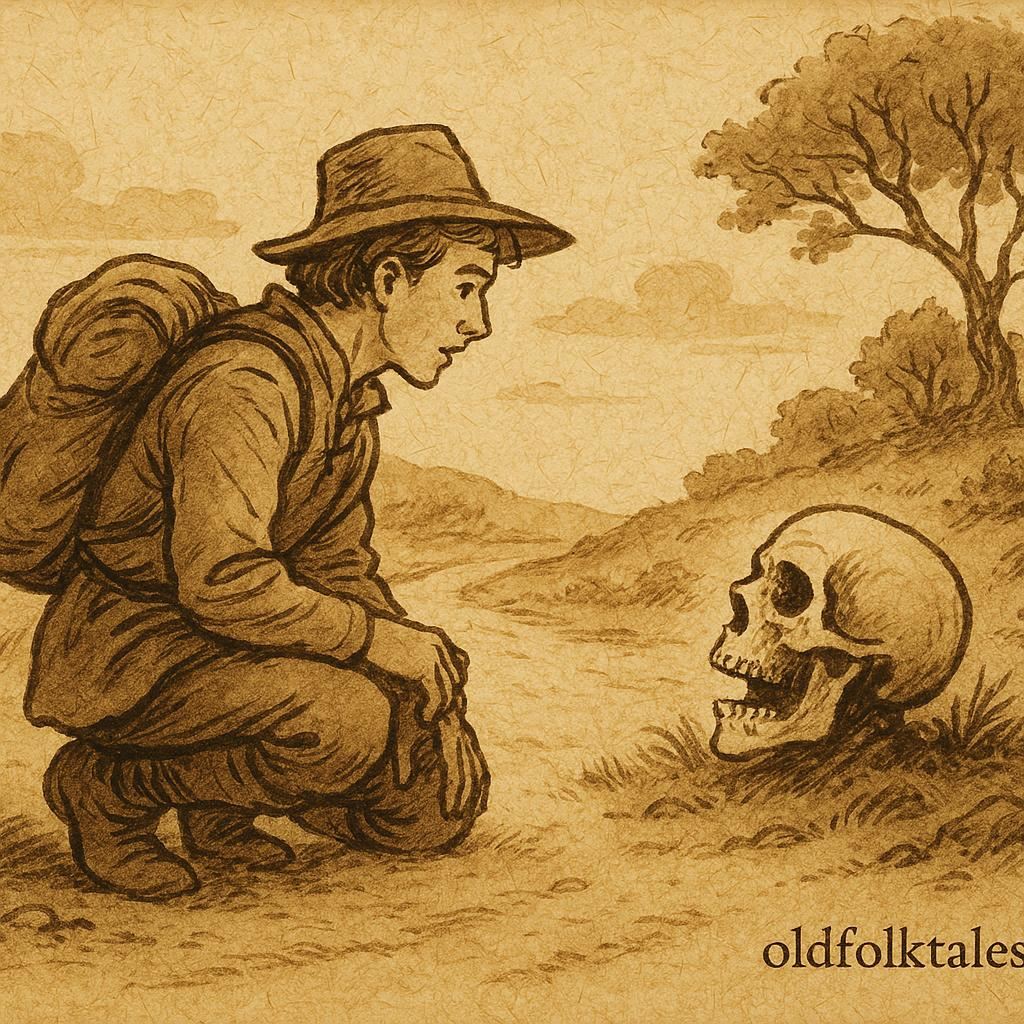

As he passed beneath a great oak tree, something pale caught his eye. Lying half-hidden among the roots was a human skull, bleached by the sun and cracked with age. The traveler bent down, brushed away the leaves, and stared curiously at it.

“How did you come to be here, old skull?” he asked, half laughing at himself for talking to bones.

To his astonishment, the skull replied in a quiet, hollow voice, “Talking brought me here.”

The traveler staggered backward, his heart pounding. “You can talk?” he gasped. But the skull said nothing more. He circled it, poked it with a stick, but it remained still. Convinced that he had heard a spirit’s voice, the traveler turned and ran down the road as fast as his legs could carry him.

Explore Native American beings, swamp creatures, and modern cryptid sightings across the country.

The King’s Judgment

In the next village, the traveler burst into the royal courtyard, breathless and wild-eyed. “Your Majesty! Your Majesty!” he cried. “There’s a talking skull by the big oak tree!”

The king, seated beneath his parasol of palm leaves, frowned. “A talking skull?” he repeated. “Do you take me for a fool? Skulls do not talk.”

“It’s true, Your Majesty! I spoke to it myself,” the traveler insisted. “It said, ‘Talking brought me here.’”

The king’s face hardened. “If this is some trick to make sport of me, you will lose your head. But if you speak truth, I will reward you with gold and land. Show me this talking skull.”

And so, with the king’s guards and servants behind them, the traveler led the royal procession back to the great oak tree.

The Silent Skull

The skull still lay in the same place. The traveler pointed eagerly. “There it is, Your Majesty! Watch, it will speak again.”

The king folded his arms. “Then make it speak.”

The traveler knelt beside the skull and whispered, “Old skull, tell the king what you told me.”

Silence.

He tried again, louder this time. “Old skull, please, speak! Tell the king how you came here!”

The skull remained still. The forest was quiet except for the cry of a crow far away.

“Perhaps it is shy before the king,” the traveler said nervously. “It spoke to me when we were alone.”

The king’s patience broke. “Enough lies!” he thundered. “You waste my time and insult my crown.”

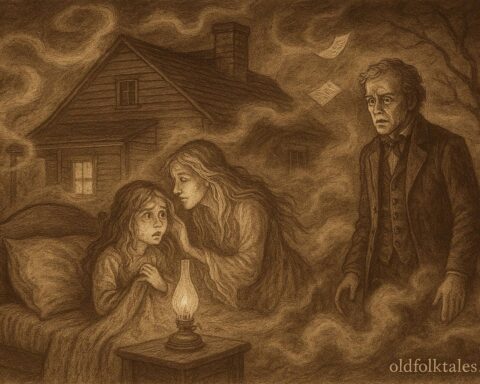

Before the traveler could plead, the guards seized him. “If you love talking so much,” the king said coldly, “you shall talk no more.” With a swift stroke, the traveler’s head was severed.

The Skull’s Final Words

When the king and his men rode away, the forest returned to stillness. The traveler’s head rolled near the skull that had lured him into doom.

Moments later, the skull’s empty eyes seemed to gleam with faint light. In a hollow voice it whispered, “Talking brought you here too.”

And then, silence fell once more.

Discover African American wisdom, Native American spirit stories, and the humor of early pioneers in American Folktales.

Moral Lesson

The Talking Skull teaches a lasting truth: not every thought needs to be spoken, and careless words can bring great trouble. Wisdom often lies in silence. The traveler’s fate reminds us that speech can be a gift or a curse, depending on how—and when—it is used.

Knowledge Check

1. What is the main lesson of “The Talking Skull” folktale?

The story warns that talking too much or speaking without thought can lead to one’s downfall, showing that silence is often wiser.

2. Who collected the “Talking Skull” folktale in America?

It was collected by Zora Neale Hurston in Mules and Men (1935) and traces back to West African oral traditions.

3. What does the talking skull symbolize in the story?

The skull represents wisdom gained too late, reminding people that loose speech can bring destruction.

4. Why does the king execute the traveler?

The king believes the traveler lied about the talking skull, showing how words can cause fatal misunderstandings.

5. What is the origin of the “Talking Skull” folktale?

It originated from African (Akan/Ashanti) storytelling traditions and was preserved through African-American oral culture in the U.S. South.

6. How does the story of the Talking Skull reflect African moral traditions?

It mirrors African proverbs that value restraint, respect for elders, and the belief that words carry power, both to create and destroy.

Source: Adapted from traditional African-American folktales with West African (Akan/Ashanti) roots, collected by Zora Neale Hurston in Mules and Men (1935).

Cultural Origin: African-American folklore, with origins in West Africa.