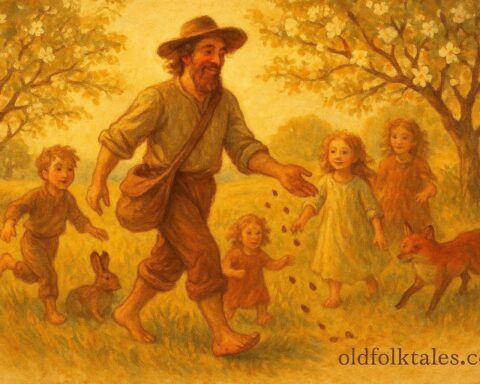

In the quiet farmlands of Pennsylvania, where morning mist drifts over wooden barns and church bells echo through rolling valleys, a sacred practice once thrived among the Pennsylvania Dutch, descendants of German immigrants who carried their faith, language, and healing traditions across the Atlantic. This practice was called Braucherei, or Powwow, a form of folk magic deeply rooted in Christian belief and centuries of Germanic wisdom.

The word Powwow had nothing to do with Native American ceremonies; rather, it was the English rendering of “Braucherei,” meaning “to use” or “to apply.” For the brauchers, the folk healers, it meant applying faith through words, prayers, and sacred symbols to bring comfort and healing. These healers lived humbly, often working as farmers or craftspeople by day, but when illness or injury struck, neighbours would come knocking at their doors, seeking the blessing of their ancient prayers.

One of the most famous of these powwow charms was a prayer used to stop bleeding. The braucher would press a clean cloth over the wound and recite in a calm, steady voice:

“Blood, stay in thy veins,

As Christ stayed in His grave

Till the third day.

In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, Amen.”

To the onlooker, it may have seemed like a simple prayer. But within its words lay generations of belief, the faith that divine power flowed through the spoken word, just as blood flowed through the veins. The charm invoked the mystery of Christ’s resurrection, reminding the wounded that just as life was restored to Him, so too could health return to the body.

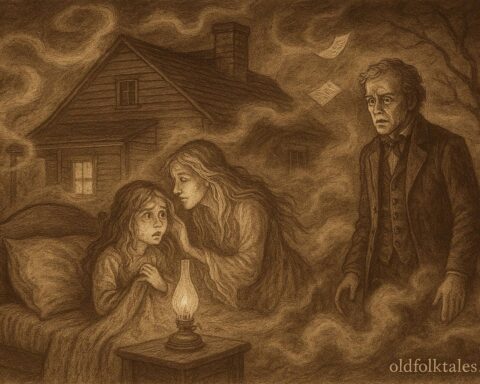

In Braucherei, healing was never separate from faith. The braucher would often make the sign of the cross three times over the injury, whispering quietly so that only God could hear the rest of the words. To the people of those Pennsylvania valleys, such gestures were as natural as taking medicine, for they believed that healing was both a physical and a spiritual act.

The tools of powwow were simple yet sacred. A well-worn Bible, a small pouch of herbs, and a few handwritten verses known as himmelsbrief, or “heavenly letters”, often hung above doors or tucked into clothing. These amulets were believed to offer divine protection against illness, fire, or misfortune. The verses, copied carefully by hand, were never sold for money. A braucher who tried to profit from them risked losing their gift, for powwow was an act of service, not trade.

The practice reflected a delicate blend of Christian devotion and folk magic. Though outsiders sometimes misunderstood it, for the Pennsylvania Dutch it was an extension of faith, a way of living close to God’s creation. Their world was filled with signs and sacred correspondences: herbs carried healing virtues because God placed them there; words held power because He gave them breath; and every prayer, when spoken with sincerity, became a bridge between heaven and earth.

Through the centuries, The Long Lost Friend, a small book written by Johann George Hohman in 1820, became the heart of Braucherei tradition. Passed from one generation to another, it contained recipes, blessings, and prayers, charms for healing burns, stopping bleeding, and warding off evil. To own a copy was to possess a friend indeed, for many believed the book itself held protective power. Families treasured it, wrapping it in cloth and storing it beside their Bibles, knowing it preserved not only remedies but a connection to their ancestors.

While some considered powwow a form of “white magic,” its practitioners insisted it was Christian work, “faith healing,” guided by the Holy Trinity. They saw themselves as humble instruments, never as sorcerers. “It is not my hand that heals,” a braucher might say, “but God’s hand through me.”

Even today, echoes of Braucherei can still be found in rural Pennsylvania. Though few still practice it openly, some elders remember the healing prayers spoken by their grandmothers over a cut or fevered child. The words, whispered softly in both English and the old Pennsylvania Dutch dialect, remind those who hear them that healing is not only about the body, but also about the soul’s connection to something greater.

The Braucherei “Powwow” Healing Prayer stands as a living testament to faith interwoven with folklore, a legacy of immigrants who brought their spiritual medicine to a new land and made it flourish amid fields, mountains, and simple hearts.

Click to read all American Traditions & Beliefs — the living folklore of daily life, customs, and superstitions.

Moral Lesson

The story of the Braucherei “Powwow” Healing Prayer teaches that faith and compassion can heal as powerfully as any medicine. True healing arises when belief, kindness, and the natural world unite in harmony.

Knowledge Check

1. What does “Braucherei” or “Powwow” mean?

It refers to a Pennsylvania Dutch folk healing practice that combines Christian prayer, herbal medicine, and traditional charms.

2. Who were the “brauchers”?

They were folk healers who used spiritual prayers, herbs, and written charms to heal and protect their communities.

3. What is the purpose of the healing charm recited in the story?

It was used to stop bleeding, invoking the power of Christ’s resurrection and divine faith.

4. What is a “himmelsbrief”?

A himmelsbrief is a handwritten “heavenly letter” or amulet believed to bring divine protection and healing.

5. How does The Long Lost Friend relate to Braucherei?

It is a famous 1820 book by Johann George Hohman that records traditional powwow prayers, remedies, and charms.

6. What cultural lesson does this folktale convey?

That blending faith with tradition preserves both spiritual strength and cultural identity across generations.

Source: Adapted from The Long Lost Friend by Johann George Hohman (1820), public domain.

Cultural Origin: Pennsylvania, USA (18th–19th century German-American settlers).